Kyushu Trip 2024: Kagoshima

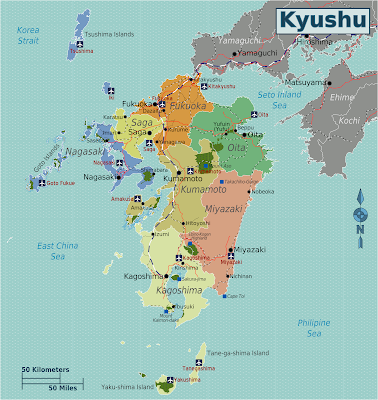

The day after going to Nagasaki, we then headed down to the south of Kyūshū to the port city of Kagoshima, which to the uninitiated probably rings fewer bells than Nagasaki would, but it's a city that bears a remarkable number of similarities. It was also a key site in the early history of Japanese Christianity, an early centre of industrialisation, and a place of great significance to the broader Meiji Restoration period.

For a quick rundown, Kagoshima was where the first Jesuit missionary to Japan, St Francis Xavier, landed in 1549. At this time it served as the seat of power for the Shimazu clan during the Sengoku era, and was then the capital of the Shimazu-ruled Satsuma Domain during the Edo period. In retaliation for Satsuma's implicit support of radical samurai assassins, the Royal Navy bombarded Kagoshima in August 1863, but paradoxically served to empower more pro-foreign elements in the domain government who established an informal alliance with Britain. After serving as a key Shogunate ally down to 1864, it turned coat over the course of the next couple of years and became one of the leading domains in the anti-Tokugawa coalition and producing several key players in the state and military – particularly the navy – of the early Meiji government. Kagoshima also became the initial epicentre of the Satsuma Rebellion (a.k.a. the Southwestern (Seinan) Civil War) in January 1877, being where Saigō Takamori's samurai paramilitary were trained, but the city was left mostly unguarded when the rebels marched north, and it was captured by a government landing force barely a month after the uprising. After Saigō was defeated on the east coast, he and 500 men were able to make it back to Shiroyama, overlooking the castle, where they were wiped out to a man in September. Kagoshima's significance declined after the Satsuma Rebellion, although it housed some modern port facilities and a naval air base and was heavily bombed in June 1945. Today, Kagoshima still serves a role as a logistics hub for southern Kyūshū, but it would be fair, I think, to call it a relatively quiet city by Japanese standards.

The trip takes about the same amount of time as Nagasaki: around 90 to 110 minutes by Shinkansen, depending on which service you take. There's also a small airport – on the site of the old naval airfield – serviced mainly by regional and budget airlines.

This time, the rain and especially the wind were very much in evidence, but not to an unbearable degree. Very soon after arriving you get an immediate sense of how much significance Kagoshima – or at least the powers-that-be in charge of culture and public infrastructure – seems to value its status as the old seat of the Shimazu clan.

|

| A lantern by a bridge over the Kotsuki river, with the Shimazu clan mon prominently displayed. |

Kagoshima brands itself the 'birthplace of the Meiji Restoration', a claim I suspect that the Mōri clan of Chōshū would readily dispute, although unfortunately it turns out that the city's museum of the Meiji Restoration had been closed for renovation during the tourism off-season, something we hadn't accounted for. Nor did we recall that, this being a Monday, most museums are in fact closed unless otherwise specified, so the Reimeikan in Kagoshima Castle was also out of action. Drat!

Still, even the historical walk along the north bank of the river was a pretty interesting one. I seem to have neglected to take any photos, but there's some good signage and a few interesting odds and ends including a mosaic map showing various routes taken by prominent Satsuma individuals in the 1860s. What was also quickly noticeable was that along with Meiji Restoration personages, especially Saigō Takamori (who led the Imperial army in the early stages of the Boshin War in 1868 and then led the Satsuma Rebellion in 1877) and Ōkubo Toshimichi (Minister of the Interior in the early Meiji junta and subsequently de facto Prime Minister), there was also a bit of commemoration of someone I hadn't registered as being a native of Kagoshima, that being Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō, the victor of Tsushima.

|

| A marker for the birthplace of Admiral Tōgō |

|

| A marker for the birthplace of Saigō Takamori |

After a hearty ramen at Tontoro, advertised as one of the city's premier ramen joints, we girded ourselves for a long walk northwards along the waterfront.

Also difficult to miss, once noticed, was the presence of the Shimazu clan mon even on manhole covers:

On the way up, we passed through the Ishibashi Memorial Park, built to house three of five early 19th-century stone bridges built on the orders of Shimazu Shigehide, the other two of which had been washed out in 1993. The park and its bridges link up a number of memorials to various events in the city's history.

|

| Memorial to the war dead of the Satsuma Rebellion |

|

| A memorial depicting the arrival of St Francis Xavier. Note the Shimazu clan mon in the upper right corner! |

|

| A slightly minimalist memorial to the 'Anglo-Satsuma War' of 1863 |

|

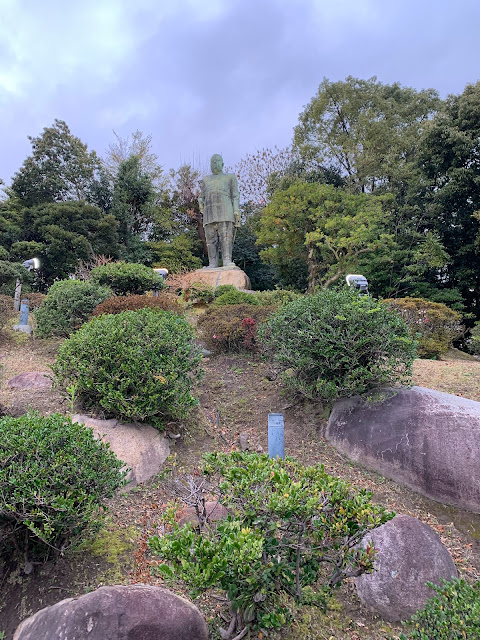

| A statue of Admiral Tōgō up on a hill which we decided was not worth the effort of climbing all the way up to. |

At the end of our half-hour trek was the Shuseikan, housing not only the clan residence of the Shimazu but also several early industrial sites, which the family decided to have built right on their own estate. For my part I had been blissfully unaware of the Shimazu clan's role as industrial investors. In a pattern that had become quite familiar, the main museum was under renovation during the low season, although the open-air portions of the site were still open to the public for a small fee.

|

| To be fair, most of what used to be the textile mill is now a carpark... |

|

| One eyes the claim that Japan's 'successful industrialisation was achieved... without colonisation' with a certain scepticism... |

|

| The remains of the old reverberatory furnace |

|

| I have to say, there is a certain je ne sais quoi about Japanese gardens in winter. The plants that remain green really do stand out against the dried grass. |

|

| The clan residence (we opted not to pay to go in.) |

|

| A panoramic view from the end of the main garden, now decorated with a piece of the wall from a Shimazu-owned electric power station. |

Taking a cab back to our hotel near the city centre, we passed by the walls of Kagoshima Castle, which as a sign noted, were still riddled with bullet holes made during the Satsuma Rebellion:

|

| Note also the Shimazu clan mon on the lamppost! |

After checking in and dropping our bags off, we made one last walk around the area of Shiroyama, where Saigō Takamori made his last stand in September 1877. First up was the Terukuni shrine, dedicated to the deified spirit of Shimazu Nariakira, the penultimate daimyō of Satsuma. Nearby were two statues depicting members of the clan: one of Nariakira's brother Hisamitsu, who partially precipitated the Namamugi Incident (or Richardson Affair) which caused the Anglo-Satsuma War; the other of Hisamitsu's son Tadayoshi, who is noted as being the first person in Japan to send a message by electric telegraph.

As we headed further towards the northeast, this statue of Saigō Takamori was just about unavoidable:

After passing a memorial to 84 Satsuma retainers who died during a river engineering project in the 1750s, we capped things off at a memorial at the site of Saigō Takamori's death, an apposite, if somewhat morbid, end to the day.

The inaccessibility of the three museums – two for unforeseen circumstances and one for circumstances that should have been more foreseen – was very unfortunate, but I think we managed to make a good showing despite that, and it was clear that in fact, had any of them been open, we'd have struggled to fit everything in. Well, at least it leaves things open for a return visit! My phone claimed I took 19,693 steps covering 12.2 kilometres, which sounds pretty plausible on its own but still reinforced my scepticism about Nagasaki, where I certainly do not remember walking nearly as much.

To end on a lighter note, in the train station the next day I took note of this rather fun souvenir on offer:

Comments

Post a Comment